Legacy of an Ecocide: Agent Orange Aftermath

“As maker and viewer, they confirm my sense of being in the world and are for me the embodiment of a prayer.” Petronella Ytsma

“These images serve both as a glimpse of the legacy we left, but more importantly, they are my testimony to the children, their families and to the mystery of what makes us human. For them and millions of others, that war is not over. They cannot close their eyes to it and simply move on. I believe it is vital that we meet their eyes and look into this mirror. May these images deny the wish to erase the past and ‘the other’ from memory.”

Artist’s Statement

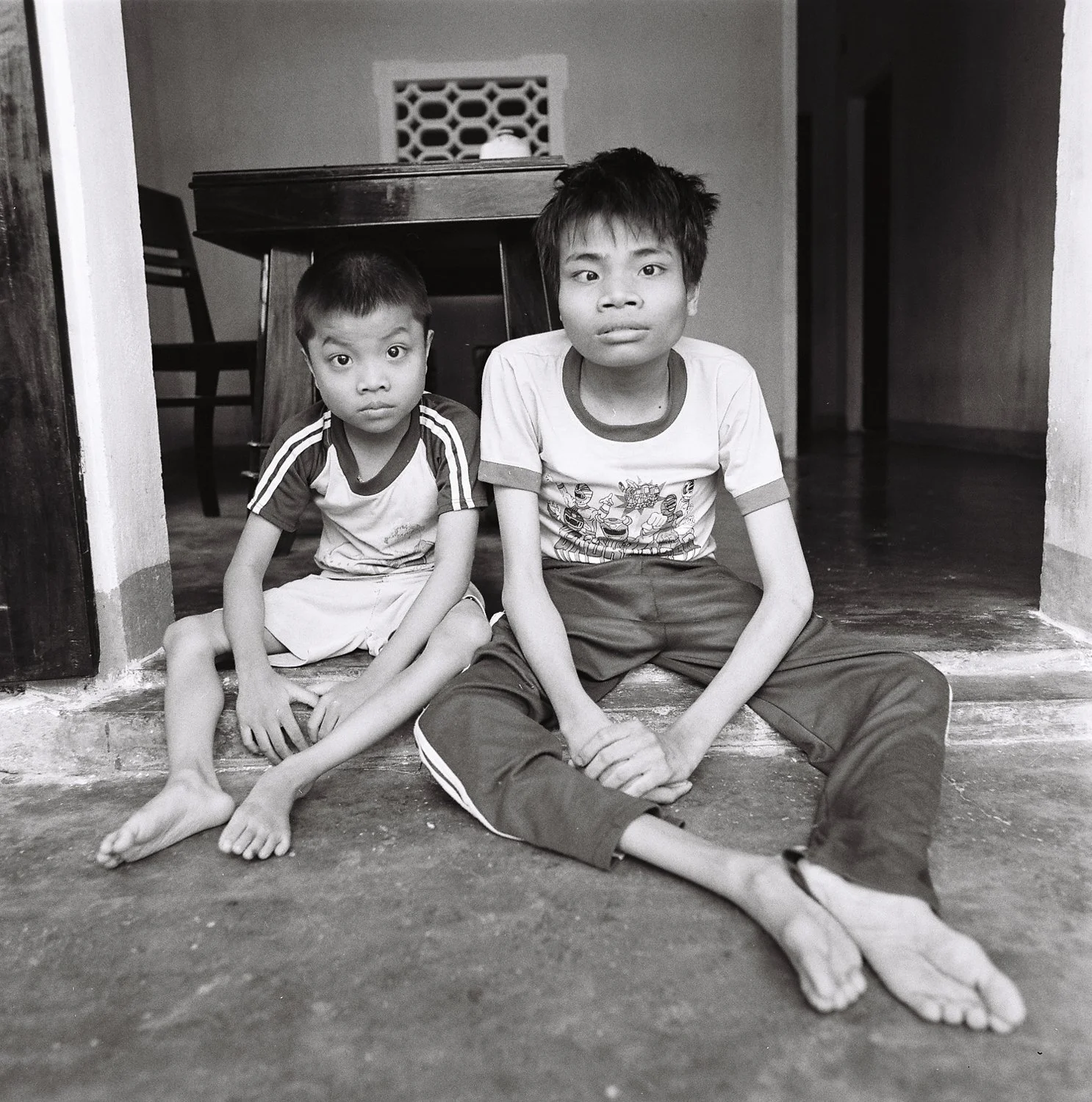

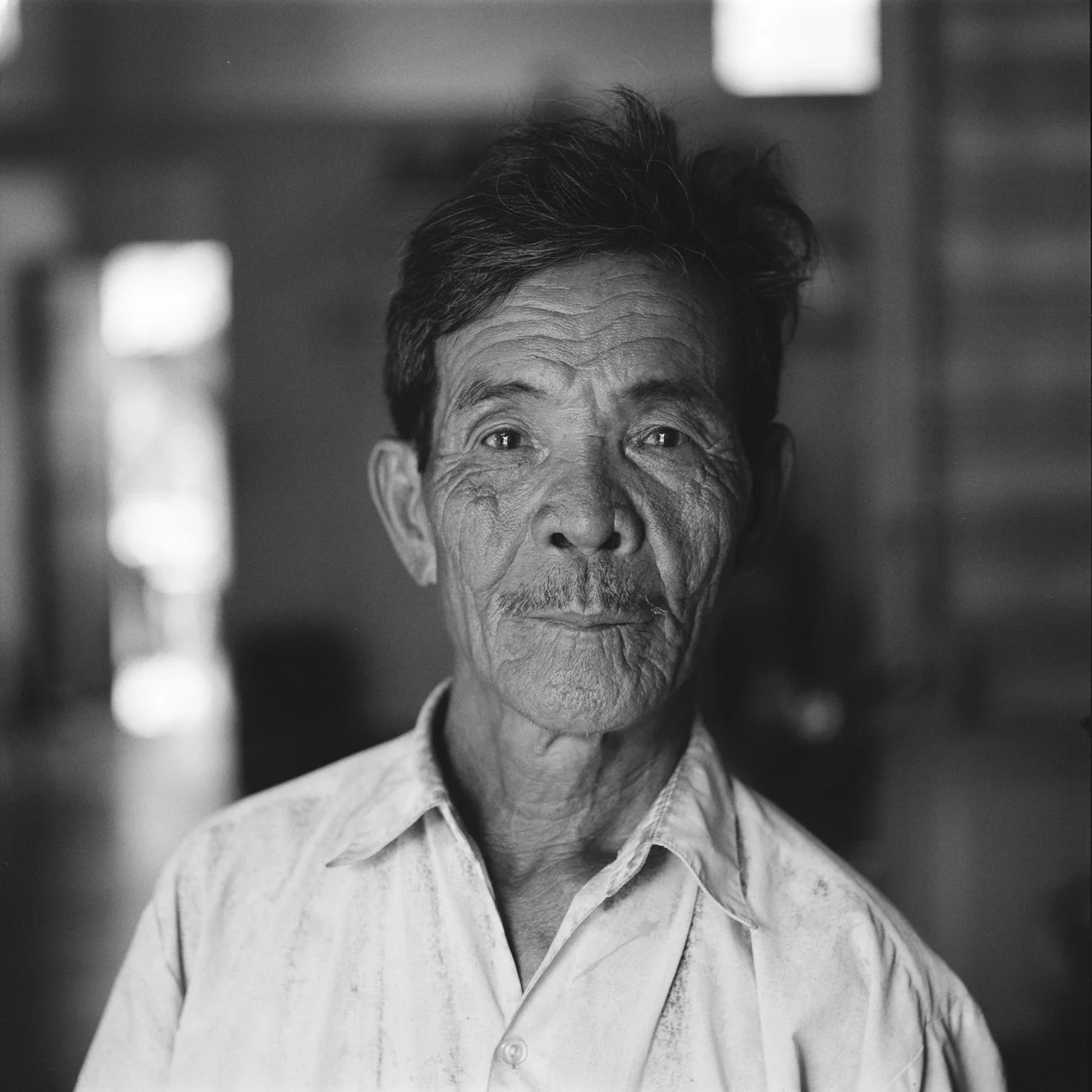

My work is concerned with social justice and ecological issues from an artistic perspective. Primarily through the lens of my Hasselblad, which allows the ‘unhurried visit’, I explore remnants and legacy, memory and mirror, and reflect on the civil contracts inherent between image maker, giver and viewer. Images from this body of work about intergenerational effects of Agent Orange on a specific population comprise a cautionary tale, a never-ending highly controversial one fraught with myriad complexities. As maker and viewer, they confirm my sense of being in the world and are for me the embodiment of a prayer.

From 1961 to 1971 the United States engaged in what can only be described as an ecocide - the most extensive and systematic use of chemical warfare in the history of mankind, for the stated purpose of defoliation in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. Much was done in secret, with full denial, and with little thought to long-term consequences on troops, local populations or environment. The most toxic of the chemicals employed was Agent Orange containing high levels of Dioxin. The Vietnamese interpret this as a reclamation chemical to ‘bare the leaves of plants for making VN to become a place of fallow hill - empty house.’ Estimates of 80 million litres (12 million gallons) were systematically used, impacting about 25% of the land in South Vietnam. It is also estimated that 4.8 million people were exposed, at least 3 million symptomatic and 85% of families having 2 or more children affected.

In 2007, and again in 2008, with the aid of a Minnesota State Arts Board grant, I spent several months in Vietnam, researching and documenting issues surrounding Agent Orange/Dioxin. I visited various ‘hot spots’, interviewing government and community officials, 75 families and several long-term care facilities, documenting many children afflicted with a wide array of disabilities attributable to effects of Dioxin. Submitted images are some of the portraits of second and third generations affected by this war that ended 38 years ago.

The relevancy of this work lies in the fact that we remain a hegemonic power heavily invested in war and chemical industrial complexes. We fool ourselves into believing that other people’s children are not as precious, or human, as our own. These images serve both as a glimpse of the legacy we left, but more importantly, they are my testimony to the children, their families and to the mystery of what makes us human. For them and millions of others, that war is not over. They cannot close their eyes to it and simply move on. I believe it is vital that we meet their eyes and look into this mirror. May these images deny the wish to erase the past and ‘the other’ from memory.

Nguyen Ngoc Tho, b. 1993

Sinh, b. 2001

Le Minh Thanh, b. 2003

Mother and Son, Nguyen Duc Tu. b. 1984

Hoc Mon, 2008

Third Generation, Nguyen Thi Chung, b. 1993

Mother and Son, Le Van Thap, b. 1990

Father and Daughters, Thi Thuong, b. 1999, Thi Nhua, b. 2001

Father and Daughters, Lam Thi Nhap b. 1969; Lam Thi Xa, b. 1971; Lam Thi Ca, b. 1973

Brothers, Tan Tri, b. 1989; Tan Han, b. 2000

Phan Van Phi, b. 1940

Mother and Son, Do Van Lan, b. 1977

Tran Do Tho Nguyen, b. 1980

Do Thi Kim Hai, b. 1976

Mother and Daughter, Ho Thi My Hoyen, b. 2000

Viet Nguyen, b. 1980

Baby , TuDu Hospital, b. 2006

Nguyen Du, b. 1993 and Uncle

Child, TuDu Hospital, 2008

Baby, TuDu Hospital, 2008

“Opening the Gates”

By Brenda Paik Sunoo, Photojournalist and Author of Vietnam Moment and Seaweed and Shamans: Inheriting the Gifts of Grief

There are gates we dare not open, often because of fear, denial guilt or shame. But when we are fortunately guided by a gentle gatekeeper we feel safe to explore neglected emotional terrain. This is how I have felt since I first met Petronella Ytsma and accompanied her on some of her visits to survivors of Agent Orange in Viet Nam.

My husband and I lived as working expats in Hanoi between September 2002 and April 2009. Through mutual friends, I was introduced to Ms. Ytsma. We both shared a passion for photography. More importantly we shared common views of social responsibility, social justice and compassion towards suffering.

Over the years, I have seen many photos of Agent Orange survivors. At one point, I had also considered doing such a project. But I could not overcome my own fears of confronting the pain and suffering of these parents and children. I realized that my own fears were partly attributed to previous images I had viewed that diminished these survivors as human beings with feelings, varying levels of capacity, unique personalities and treatable disabilities.

By contrast, Petronella’s photo essays are fearless in their confrontation with reality, and yet they are reverent, elegant, gentle and engaging. We, as visitors, are invited to meet these survivors and their families in their homes. They are intimate photos because she approached each survivor with a true sense of love and compassion and restraint when necessary.

On more than one occasion a mother broke into tears as Nell embraced her into her arms. Later, Nell reflected, “more important than my photos is the gift of being a witness, so they know that we care.”

Her integrity as an artist and her sensitivity as a human being have thus created a significant collection of photos that open the gate.